|

|

| (11 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| | <big><big>Electricity and Matter</big>[https://archive.org/details/electricitymatte00thomiala/page/n15/mode/2up]</big> |

|

| |

|

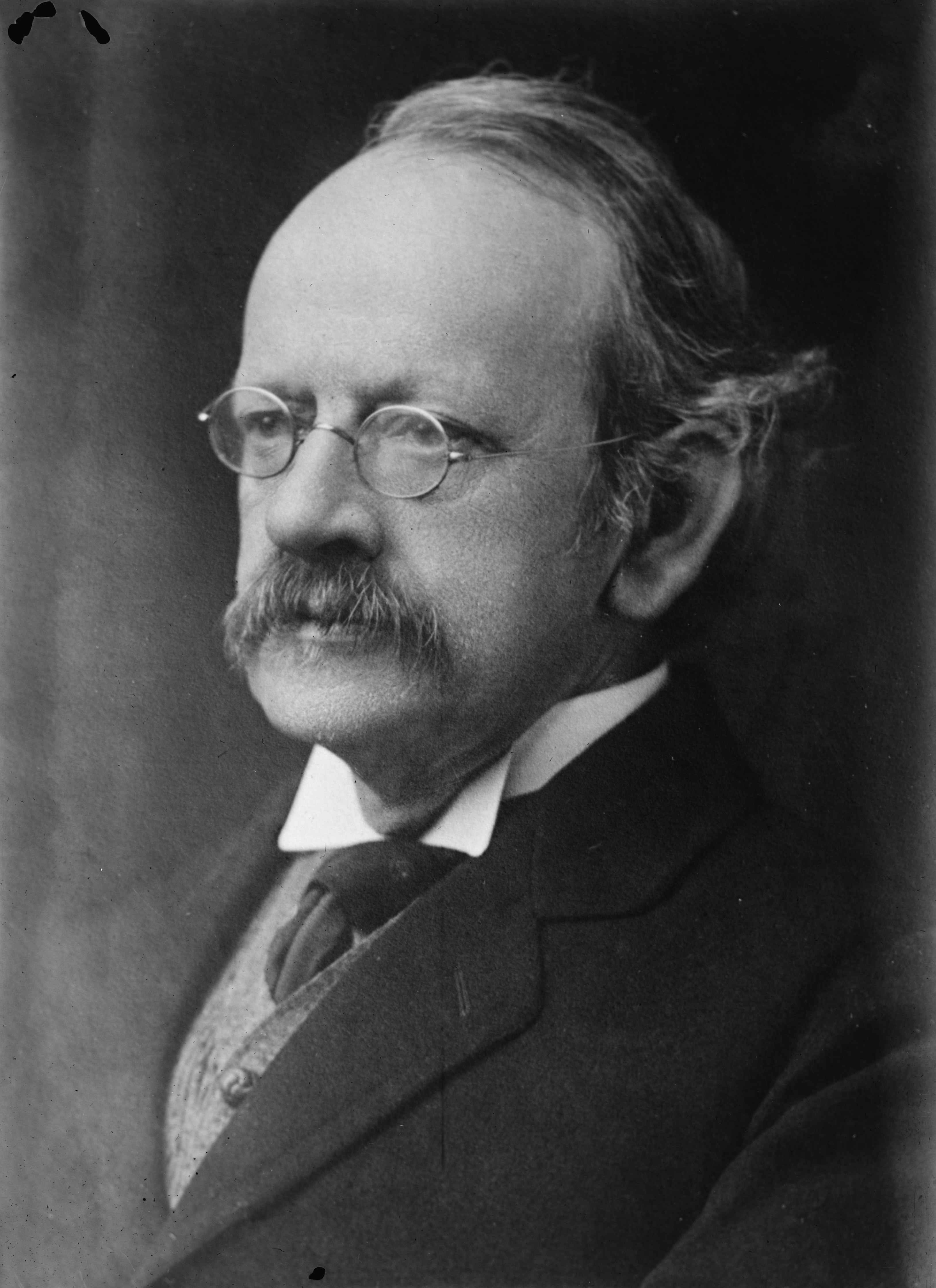

| | [[wikipedia:J. J. Thomson|J. J. Thomson]], D.Sc., LL.D., PH.D., F.R.S. |

|

| |

|

| "

| | Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge; [[wikipedia:Cavendish Professor of Physics|Cavendish Professor of Experimental Physics]], Cambridge |

|

| |

|

| J. J. THOMSON, D.Sc., LL.D., PH.D., F.R.S.

| | With Diagrams |

|

| |

|

| ""FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE; CAVENDISH PROFESSOR OF EXPERIMENTAL PHYSICS, CAMBRIDGE

| | New York |

|

| |

|

| | Charles Scribner's Sons 1904 |

|

| |

|

| WITH DIAGRAMS

| | Copyright, 1904 by [[wikipedia:Yale University|Yale University]] |

|

| |

|

| | Published, March, 1904 |

|

| |

|

| NEW YORK

| | ==The Silliman Foundation== |

|

| |

|

| CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1904

| | In the year 1883 a legacy of eighty thousand dollars was left to the President and Fellows of Yale College in the city of New Haven, to be held in trust, as a gift from her children, in memory of their beloved and honored mother Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliinan. |

|

| |

|

| | On this foundation Yale College was requested and directed to establish an annual course of lectures designed to illustrate the presence and providence, the wisdom and goodness of God, as manifested in the natural and moral world. These were to be designated as the Mrs. Hepsa Ely [[Wikipedia:Silliman Memorial Lectures|Silliman Memorial Lectures]]. It was the belief of the testator that any orderly presentation of the facts of nature or history contributed to the end of this foundation more effectively than any attempt to emphasize the elements of doctrine or of creed; and he therefore provided that lectures on dogmatic or polemical theology should be excluded from the scope of this foundation, and that the subjects should be selected rather from the domains of natural science and history, giving special prominence to astronomy, chemistry, geology, and anatomy. |

|

| |

|

| COPYRIGHT, 1904 BY YALE UNIVERSITY

| | It was further directed that each annual course should be made the basis of a volume to form part of a series constituting a memorial to Mrs. Silliman. The memorial fund came into the possession of the Corporation of Yale University in the year 1902; and the present volume constitutes the first of the series of memorial lectures. |

| | |

| Published, March, 1904

| |

| | |

| | |

| THE SILLIMAN FOUNDATION.

| |

| | |

| In the year 1883 a legacy of eighty thousand dollars was left to the President and Fellows of Yale College in the city of New Haven, to be held in trust, as a gift from her children, in memory of their beloved and honored mother Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliinan.

| |

| | |

| On this foundation Yale College was requested and directed to establish an annual course of lectures de- signed to illustrate the presence and providence, the wisdom and goodness of God, as manifested in the natural and moral world. These were to be designated as the Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliinan Memorial Lectures. It was the belief of the testator that any orderly presenta- tion of the facts of nature or history contributed to the end of this foundation more effectively than any attempt to emphasize the elements of doctrine or of creed; and he therefore provided that lectures on dog- matic or polemical theology should be excluded from the scope of this foundation, and that the subjects should be selected rather from the domains of natural science and history, giving special prominence to astronomy, chemistry, geology, and anatomy.

| |

| | |

| It was further directed that each annual course should be made the basis of a volume to form part of a series constituting a memorial to Mrs. Sillimau. The memo- rial fund came into the possession of the Corporation of Yale University in the year 1902; and the present volume constitutes the first of the series of memorial lectures.

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ==PREFACE== | | ==PREFACE== |

| | [[File:J.J. Thomson LCCN2014715407.jpg|400 px|right]] |

| | In these Lectures given at [[Wikipedia:Yale University|Yale University]] in May, 1903, I have attempted to discuss the bearing of the recent advances made in Electrical Science on our views of the Constitution of Matter and the Nature of Electricity; two questions which are probably so intimately connected, that the solution of the one would supply that of the other. A characteristic feature of recent Electrical Researches, such as the study and discovery of Cathode and Rontgen Rays and Radio-active Substances, has been the very especial degree in which they have involved the relation between Matter and Electricity. |

|

| |

|

| In these Lectures given at Yale University in May, 1903, I have attempted to discuss the bear- ing of the recent advances made in Electrical Science on our views of the Constitution of Matter and the Nature of Electricity; two questions which are probably so intimately connected, that the solution of the one would supply that of the other. A characteristic feature of recent Electri- cal Researches, such as the study and discovery of Cathode and Rontgen Rays and Radio-active Substances, has been the very especial degree in which they have involved the relation between Matter and Electricity. | | In choosing a subject for the Silliman Lectures, it seemed to me that a consideration of the bearing of recent work on this relationship might be suitable, especially as such a discussion suggests multitudes of questions which would furnish admirable subjects for further investigation by some of my hearers. |

| | |

| In choosing a subject for the Silliman Lectures, it seemed to me that a consideration of the bear- ing of recent work on this relationship might be suitable, especially as such a discussion suggests multitudes of questions which would furnish ad- mirable subjects for further investigation by some of my hearers.

| |

| | |

| Cambridge, Aug., 1903.

| |

|

| |

|

| J. J. THOMSON.

| | ::Cambridge, Aug., 1903. |

|

| |

|

| | ::J. J. Thomson |

|

| |

|

| ==CONTENTS== | | ==CONTENTS== |

|

| |

|

| CHAPTER- I

| | ;Chapter I |

| | | :[[Thomson 1904/Chapter 1|Representation of the Electric Field by Lines of Force]] |

| CHE ELECTRIC OF FORCE 1

| |

| | |

| | |

| PAGE

| |

| | |

| REPRESENTATION OF THE ELECTRIC FIELD BY LINES

| |

| | |

| | |

| CHAPTER II ELECTRICAL AND BOUND MASS 30

| |

| | |

| CHAPTER III

| |

| | |

| EFFECTS DUE TO THE ACCELERATION OF FARADAY TUBES 68

| |

| | |

| CHAPTER IV THE ATOMIC STRUCTURE OF ELECTRICITY ... 71

| |

| | |

| CHAPTER V

| |

| | |

| THK CONSTITUTION OF THE ATOM 90

| |

| | |

| CHAPTER VI

| |

| | |

| llAUIO-ACTIVITY AND RADIO-ACTIVE SUBSTANCES . . 140

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| ==CHAPTER I==

| |

| | |

| REPRESENTATION OF THE ELECTRIC FIELD BY LINES OF FORCE

| |

| | |

| MY object in these lectures is to put before you in as simple and untechnical a manner as I can some views as to the nature of electricity, of the processes going on in the electric field, and of the connection between electrical and ordinary matter which have been suggested by the results of recent investigations.

| |

| | |

| The progress of electrical science has been greatly promoted by speculations as to the nature of electricity. Indeed, it is hardly possible to overestimate the services rendered by two theories as old almost as the science itself ; I mean the theories known as the two- and the one-fluid theories of electricity.

| |

| | |

| The two-fluid theory explains the phenomena of electro-statics by supposing that in the universe there are two fluids, uncreatable and indestruc-

| |

| | |

| | |

| 2 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| tible, whose presence gives rise to electrical effects; one of these fluids is called positive, the other negative electricity, and electrical phenomena are explained by ascribing to the fluids the fol- lowing properties. The particles of the positive fluid repel each other with forces varying inversely as the square of the distance between them, as do also the particles of the negative fluid; on the other hand, the particles of the positive fluid at- tract those of the negative fluid. The attraction between two charges, m and m, of opposite signs are in one form of the theory supposed to be exactly equal to the repulsion between two charges, m and m of the same sign, placed in the same position as the previous charges. In an- other development of the theory the attraction is supposed to slightly exceed the repulsion, so as to afford a basis for the explanation of gravitation.

| |

| | |

| The fluids are supposed to be exceedingly mo- bile and able to pass with great ease through con- ductors. The state of electrification of a body is determined by the difference between the quanti- ties of the two electric fluids contained by it ; if it contains more positive fluid than negative it is positively electrified, if it contains equal quantities it is uncharged. Since the fluids are uncreatable

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 3

| |

| | |

| and indestructible, the appearance of the positive fluid in one place must be accompanied by the departure of the same quantity from some other place, so that the production of electrification of one sign must always be accompanied by the pro- duction of an equal amount of electrification of the opposite sign.

| |

| | |

| On this view, every body is supposed to con- sist of three things : ordinary matter, positive elec- tricity, negative electricity. The two latter are supposed to exert forces on themselves and on each other, but in the earlier form of the theory no action was contemplated between ordinary matter and the electric fluids ; it was not until a comparatively recent date that Helmholtz intro- duced the idea of a specific attraction between ordinary matter and the electric fluids. He did this to explain what is known as contact electricity, i.e., the electrical separation produced when two metals, say zinc and copper, are put in contact with each other, the zinc becoming positively, the copper negatively electrified. Helmholtz sup- posed that there are forces between ordinary mat- ter and the electric fluids varying for different kinds of matter, the attraction of zinc for positive electricity being greater than that of copper, so

| |

| | |

| | |

| 4 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| that when these metals are put in contact the zinc robs the copper of some of its positive electricity.

| |

| | |

| There is an indefiniteness about the two-fluid theory which may be illustrated by the considera- tion of an unelectriEed body. All that the two- fluid theory tells us about such a body is that it contains equal quantities of the two fluids. It gives no information about the amount of either; indeed, it implies that if equal quantities of the two are added to the body, the body will be unaltered, equal quantities of the two fluids exactly neutraliz- ing each other. If we regard these fluids as being anything more substantial than the mathematical symbols + and — this leads us into difficulties ; if we regard them as physical fluids, for example, we have to suppose that the mixture of the two fluids in equal proportions is something so devoid of physical properties that its existence has never been detected.

| |

| | |

| The other fluid theory — the one-fluid theory of Benjamin Franklin — is not open to this objection. On this view there is only one electric fluid, the positive ; the part of the other is taken by ordi- nary matter, the particles of which are supposed to repel each other and attract the positive fluid,

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 5

| |

| | |

| just as the particles of the negative fluid do on the two-fluid theory. Matter when unelectrified is supposed to be associated with just so much of the electric fluid that the attraction of the matter on a portion of the electric fluid outside it is just sufficient to counteract the repulsion exerted on the same fluid by the electric fluid associated with the matter. On this view, if the quantity of mat- ter in a body is known the quantity of electric fluid is at once determined.

| |

| | |

| The services which the fluid theories have ren- dered to electricity are independent of the notion of a fluid with any physical properties ; the fluids were mathematical fictions, intended merely to give a local habitation to the attractions and repulsions existing between electrified bodies, and served as the means by which the splendid mathematical development of the theory of forces varying in- versely as the square of the distance which was inspired by the discovery of gravitation could be brought to bear on electrical phenomena. As long as we confine ourself to questions which only involve the law of forces between electrified bodies, and the simultaneous production of equal quantities of -{- and — electricity, both theories must give the same results and there can be nothing to

| |

| | |

| | |

| g ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| decide between them. The physicists and mathe- maticians who did most to develop the "Fluid Theories " confined themselves to questions of this kind, and refined and idealized the conception of these fluids until any reference to their physical properties was considered almost indelicate. It is not until we investigate phenomena which involve the physical properties of the fluid that we can hope to distinguish between the rival fluid the- ories. Let us take a case which has actually arisen. We have been able to measure the masses associated with given charges of electricity in gases at low pressures, and it has been found that the mass associated with a positive charge is im- mensely greater than that associated with a nega- tive one. This difference is what we should expect on Franklin's one-fluid theory, if that theory were modified by making the electric fluid correspond to negative instead of positive elec- tricity, while we have no reason to anticipate so great a difference on the two-fluid theory. We shall, I am sure, be struck by the similarity be- tween some of the views which we are led to take by the results of the most recent researches with those enunciated by Franklin in the very infancy of the subject.

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 7

| |

| | |

| Faraday's Line of Force Theoi^y

| |

| | |

| The fluid theories, from their very nature, imply the idea of action at a distance. This idea, al- though its convenience for mathematical analysis has made it acceptable to many mathematicians, is one which many of the greatest physicists have felt utterly unable to accept, and have devoted much thought and labor to replacing it by some- thing involving mechanical continuity. Pre-emi- nent among them is Faraday. Faraday was deeply influenced by the axiom, or if you prefer it, dogma that matter cannot act where it is not. Faraday, who possessed, I believe, almost unrivalled mathe- matical insight, had had no training in analysis, so that the convenience of the idea of action at a distance for purposes of calculation had no chance of mitigating the repugnance he felt to the idea of forces acting far away from their base and with no physical connection with their origin. He therefore cast about for some way of picturing to himself the actions in the electric field which would get rid of the idea of action at a distance, and replace it by one which would bring into prominence some continuous connection between the bodies exerting the forces. He was able to

| |

| | |

| | |

| g ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| do this by the conception of lines of force. As I shall have continually to make use of this method, and as I believe its powers and possibilities have never been adequately realized, I shall devote some time to the discussion and development of this conception of the electric field.

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. i.

| |

| | |

| The method was suggested to Faraday by the consideration of the lines of force round a bar magnet. If iron filings are scattered on a smooth surface near a magnet they arrange themselves as in Fig. 1 ; well-marked lines can be traced run-

| |

| | |

| | |

| LIXES OF FORCE 9

| |

| | |

| ning from one pole of the magnet to the other ; the direction of these lines at any point coincides with the direction of the magnetic force, while the intensity of the force is indicated by the concen- tration of the lines. Starting from any point in the field and travelling always in the direction of the magnetic force, we shall trace out a line which will not stop until we reach the negative pole of the magnet ; if such lines are drawn at all points in the field, the space through which the magnetic field extends will be filled with a system of lines, giving the space a fibrous structure like that pos- sessed by a stack of hay or straw, the grain of the structure being along the lines of force. I have spoken so far only of lines of magnetic force ; the same considerations will apply to the electric field, and we may regard the electric field as full of lines of electric force, which start from positively and end on negatively electrified bodies. Up to this point the process has been entirely geometri- cal, and could have been employed by those who looked at the question from the point of view of action at a distance; to Faraday, however, the lines of force were far more than mathematical abstractions — they were physical realities. Fara- day materialized the lines of force and endowed

| |

| | |

| | |

| 1Q ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| them with physical properties so as to explain the phenomena of the electric field. Thus he sup- posed that they were in a state of tension, and that they repelled each other. Instead of an in- tangible action at a distance between two electri- fied bodies, Faraday regarded the whole space between the bodies as full of stretched mutually repellent springs. The charges of electricity to which alone an interpretation had been given on the fluid theories of electricity were on this view just the ends of these springs, and an electric charge, instead of being a portion of fluid confined to the electrified body, was an extensive arsenal of springs spreading out in all directions to all parts of the field.

| |

| | |

| To make our ideas clear on this point let us consider some simple cases from Faraday's point of view. Let us first take the case of two bodies with equal and opposite charges, whose lines of force are shown in Fig. 2. You notice that the lines of force are most dense along A B, the line joining the bodies, and that there are more lines of force on the side of A nearest to B than on the opposite side. Consider the effect of the lines of force on A ; the lines are in a state of tension and are pulling away at -4; as there

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE H

| |

| | |

| are more pulling at A on the side nearest to B than on the opposite side, the pulls on A toward B overpower those pulling A away from B, so that A will tend to move toward B] it was in this way that Faraday pictured to himself the attraction between oppositely electrified bodies. Let us now consider the condition of one of the curved lines of force, such as PQ\ it is in a state

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. 2.

| |

| | |

| of tension and will therefore tend to straighten itself, how is it prevented from doing this and maintained in equilibrium in a curved position? We can see the reason for this if we remember that the lines of force repel each other and that the lines are more concentrated in the region be- tween PQ and AB than on the other side of PQ] thus the repulsion of the lines inside PQ will be greater than the repulsion of those out- side and the line PQ will be bent outwards.

| |

| | |

| | |

| 12 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| Let us now pass from the case of two oppositely electrified bodies to that of two similarly elec- trified ones, the lines of force for which are shown in Fig. 3. Let us suppose A and B are positively electrified; since the lines of force start from positively and end on negatively electrified bodies, the lines starting from A and B will travel away to join some body or bodies possessing the

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. 3.

| |

| | |

| negative charges corresponding to the positive ones on A and B] let us suppose that these charges are a considerable distance away, so that the lines of force from A would, if B were not present, spread out, in the part of the field under consideration, uniformly in all directions. Consider now the effect of making the system of lines of force attached to A and B approach each other ;

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE

| |

| | |

| | |

| since these lines repel each other the lines of force on the side of A nearest B will be pushed to the opposite side of A, so that the lines of force will now be densest on the far side of A ; thus the pulls exerted on A in the rear by the lines of force will be greater than those in the front and the result will be that A will be pulled away from B. We notice that the mechanism produc- ing this repulsion is of exactly the same type as that which produced the attraction in the pre- vious case, and we may if we please regard the repulsion between A and B as due to the attrac- tions on A and B of the complementary negative charges which must exist in other parts of the field.

| |

| | |

| The results of the repul- sion of the lines of force are clearly shown in the case represented in Fig. 4, that of two oppositely electrified plates; you will notice that

| |

| | |

| the lines of force between

| |

| | |

| PIG. 4. the plates are straight except

| |

| | |

| near the edges of the plates ; this is what we should expect as the downward pressure exerted

| |

| | |

| | |

| J4 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| by the lines of force above a line in this part of the field will be equal to the upward pressure exerted by those below it. For a line of force near the edge of the plate, however, the pressure of the lines of force below will exceed the press- ure from those above, and the line of force will bulge out until its curvature and tension counter- act the squeeze from inside ; this bulging is very plainly shown in Fig. 4.

| |

| | |

| So far our use of the lines of force has been descriptive rather than metrical ; it is, however, easy to develop the method so as to make it metrical. We can do this by introducing the idea of tubes of force. If through the boundary of any small closed curve in the electric field we draw the lines of force, these lines will form a tubular surface, and if we follow the lines back to the positively electrified surface from which they start and forward on to the negatively electrified surface on which they end, we can prove that the positive charge enclosed by the tube at its origin is equal to the negative charge enclosed by it at its end. By properly choosing the area of the small curve through which we draw the lines of force, we may arrange that the charge enclosed by the tube is equal to the unit charge. Let us call

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 15

| |

| | |

| such a tube a Faraday tube — then each unit of positive electricity in the field may be regarded as the origin and each unit of negative electricity as the termination of a Faraday tube. We regard these Faraday tubes as having direction, their di- rection being the same as that of the electric force, so that the positive direction is from the positive to the negative end of the tube. If we draw any closed surface then the difference between the number of Faraday tubes which pass out of the surface and those which pass in will be equal to the algebraic sum of the charges inside the surface; this sum is what Maxwell called the electric displace- ment through the surface. What Maxwell called the electric displacement in any direction at a point is the number of Faraday tubes which pass through a unit area through the point drawn at right angles to that direction, the number being reckoned algebraically ; i.e., the lines which pass through in one direction being taken as positive, while those which pass through in the opposite direction are taken as negative, and the number passing through the area is the difference between the number passing through positively and the number passing through negatively.

| |

| | |

| For my own part, I have found the conception

| |

| | |

| | |

| IQ ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| of Faraday tubes to lend itself much more readily to the formation of a mental picture of the proc- esses going on in the electric field than that of electric displacement, and have for many years abandoned the latter method.

| |

| | |

| Maxwell took up the question of the ten- sions and pressures in the lines of force in the electric field, and carried the problem one step further than Faraday. By calculating the amount of these tensions he showed that the mechanical effects in the electrostatic field could be explained by supposing that each Faraday tube force exerted a tension equal to R, H being the intensity of the electric force, and that, in addition to this tension, there was in the medium through which the tubes pass a hydrostatic pressure equal to \NR, N being the density of the Faraday tubes; i.e., the number passing through a unit area drawn at right angles to the electric force. If we consider the effect of these tensions and pressure on a unit volume of the medium in the electric field, we see that they are equivalent to a tension \ NR along the direction of the electric force and an equal pressure in all directions at right angles to that force.

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE

| |

| | |

| | |

| 17

| |

| | |

| | |

| Moving Faraday Tubes

| |

| | |

| Hitherto we have supposed the Faraday tubes to be at rest, let us now proceed to the study of the effects produced by the motion of those tubes. Let us begin with the consideration of a very simple case — that of two parallel plates, A and B, charged, one with positive the other with negative electricity, and suppose that after being charged the plates are con- nected by a conducting wire, EFG. This wire will pass through some of the outlying tubes ; these tubes, when in a conductor, contract to molecular dimensions and the repul- sion they previously exerted on neighboring tubes will therefore disappear. Consider the effect of this on a tube PQ between the plates ; PQ was originally in equilibrium under its own tension, and the repulsion exerted by the neighboring tubes. The repulsions due to those cut by E F G have now, however, disappeared so that PQ will no longer be in equilibrium, but will be pushed towards EFG. Thus, more and more tubes will be pushed into E FG, and we shall

| |

| | |

| | |

| F FIG. 5.

| |

| | |

| | |

| jg ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| have a movement of the whole set of tubes be- tween the plates toward E F G. Thus, while the discharge of the plates is going on, the tubes be- tween the plates are moving at right angles to themselves. What physical effect accompanies this movement of the tubes ? The result of con- necting the plates by E F G is to produce a cur- rent of electricity flowing from the positively charged plate through E F G to the negatively charged plate ; this is, as we know, accompanied by a magnetic force between the plates. This magnetic force is at right angles to the plane of the paper and equal to 47r times the intensity of the current in the plate, or, if a- is the density of the charge of electricity on the plates and v the velocity with which the charge moves, the mag- netic force is equal to kiro-v.

| |

| | |

| Here we have two phenomena which do not take place in the steady electrostatic field, one the movement of the Faraday tubes, the other the existence of a magnetic force; this suggests that there is a connection between the two, and that motion of the Faraday tubes is accompanied by the production of magnetic force. I have fol- lowed up the consequences of this supposition and have shown that, if the connection between the

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 19

| |

| | |

| magnetic force and the moving tubes is that given below, this view will account for Ampere's laws connecting current and magnetic force, and for Faraday's law of the induction of currents. Max- well's great contribution to electrical theory, that variation in the electric displacement in a dielec- tric produces magnetic force, follows at once from this view. For, since the electric displacement is measured by the density of the Faraday tubes, if the electric displacement at any place changes, Faraday tubes must move up to or away from the place, and motion of Faraday tubes, by hypoth- esis, implies magnetic force.

| |

| | |

| The law connecting magnetic force with the motion of the Faraday tubes is as follows : A Faraday tube moving with velocity v at a point P, produces at P a magnetic force whose magni- tude is 4?r v sin 0, the direction of the magnetic force being at right angles to the Faraday tube, and also to its direction of motion ; 6 is the angle between the Faraday tube and the direction in which it is moving. We see that it is only the motion of a tube at right angles to itself which produces magnetic force; no such force is produced by the gliding of a tube along its length.

| |

| | |

| | |

| 20 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| Motion of a Charged Sphere

| |

| | |

| We shall apply these results to a very simple and important case — the steady motion of a charged sphere. If the velocity of the sphere is small compared with that of light then the Fara- day tubes will, as when the sphere is at rest, be uniformly distributed and radial in direction. They will be carried along with the sphere. If e is the charge on the sphere, 0 its centre, the

| |

| | |

| density of the Faraday tubes at P is TTp*'

| |

| | |

| so that if v is the velocity of the sphere, 6 the

| |

| | |

| | |

| angle between OP and the direction of motion of the sphere, then, according to the above rule, the

| |

| | |

| magnetic force at P will be 6V *™ °, the direc- tion of the force will be at right angles to OP, and at right angles to the direction of motion of the sphere; the lines of magnetic force will thus

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 21

| |

| | |

| be circles, having their centres on the path of the centre of the sphere and their planes at right angles to this path. Thus, a moving charge of electricity will be accompanied by a magnetic field. The existence of a magnetic field implies energy; we know that in a unit volume of the field at a place where the magnetic force is H

| |

| | |

| there are ~— units of energy, where /x is the

| |

| | |

| O7T

| |

| | |

| magnetic permeability of the medium. In the case of the moving sphere the energy per unit

| |

| | |

| D . a^v* sin20 ,- , . .

| |

| | |

| volume at P is i—= — Typr- Taking the sum of

| |

| | |

| this energy for all parts of the field outside the

| |

| | |

| sphere, we find that it amounts to ~- , where a

| |

| | |

| 3a

| |

| | |

| is the radius of the sphere. If m is the mass of the sphere, the kinetic energy in the sphere is £ m v9 ; in addition to that we have the energy outside the sphere, which as we have seen is

| |

| | |

| £-z — ; so that the whole kinetic energy of the od

| |

| | |

| (2u £2\ m -\- -o- ~~ i 0*, or the energy is

| |

| | |

| the same as if the mass of the sphere were

| |

| | |

| 2u, 62

| |

| | |

| m -f- -£• - instead of m. Thus, in consequence of o a

| |

| | |

| | |

| 22 ELECTRICITY AND MATTKK

| |

| | |

| the electric charge, the mass of the sphere is

| |

| | |

| ~&^L^AAoL_ 9,1 $

| |

| | |

| measured by -^—. This is a very important re- sult, since it shows that part of the mass of a charged sphere is due to its charge. I shall later on have to bring before you considerations which show that it is not impossible that the whole mass of a body may arise in the way.

| |

| | |

| Before passing on to this point, however, I should like to illustrate the increase which takes place in the mass of the sphere by some analogies drawn from other branches of physics. The first of these is the case of a sphere moving through a frictionless liquid. When the sphere moves it sets the fluid around it moving with a velocity propor- tioned to its own, so that to move the sphere we we have not merely to move the substance of the sphere itself, but also the liquid around it ; the consequence of this is, that the sphere behaves as if its mass were increased by that of a certain vol- ume of the liquid. This volume, as was shown by Green in 1833, is half the volume of the sphere. In the case of a cylinder moving at right angles to its length, its mass is increased by the mass of an equal volume of the liquid. In the case of an elongated body like a cylinder, the amount by

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 23

| |

| | |

| which the mass is increased depends upon the di- rection in which the body is moving, being much smaller when the body moves point foremost than when moving sideways. The mass of such a body depends on the direction in which it is moving.

| |

| | |

| Let us, however, return to the moving electri- fied sphere. We have seen that in consequence of

| |

| | |

| its charge its mass is increased by -(*— ; thus, if it

| |

| | |

| oa

| |

| | |

| is moving with the velocity v, the momentum is not mv, but / m -f- "^ — j v. The additional mo-

| |

| | |

| mentum - — v is not in the sphere, but in the space

| |

| | |

| surrounding the sphere. There is in this space ordinary mechanical momentum, whose resultant is

| |

| | |

| | |

| v and whose direction is parallel to the di-

| |

| | |

| rection of motion of the sphere. It is important to bear in mind that this momentum is not in any way different from ordinary mechanical momen- tum and can be given up to or taken from the momentum of moving bodies. I want to bring the existence of this momentum before you as vividly and forcibly as I can, because the recogni- tion of it makes the behavior of the electric field

| |

| | |

| | |

| 24 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| entirely analogous to that of a mechanical sys- tem. To take an example, according to Newton's Third Law of Motion, Action and Reaction are equal and opposite, so that the momentum in any direction of any self-contained system is invariable. Now, in the case of many electrical systems there are apparant violations of this principle ; thus, take the case of a charged body at rest struck by an electric pulse, the charged body when exposed to the electric force in the pulse acquires velocity and momentum, so that when the pulse has passed over it, its momentum is not what it was origi- nally. Thus, if we confine our attention to the momentum in the charged body, i.e., if we suppose that momentum is necessarily confined to what we consider ordinary matter, there has been a viola- tion of the Third Law of Motion, for the only momentum recognized on this restricted view has been changed. The phenomenon is, however, brought into accordance with this law if we recog- nize the existence of the momentum in the electric field ; for, on this view, before the pulse reached the charged body there was momentum in the pulse, but none in the body; after the pulse passed over the body there was some momentum in the body and a smaller amount in the pulse,

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 25

| |

| | |

| the loss of momentum in the pulse being equal to the gain of momentum by the body.

| |

| | |

| We now proceed to consider this momentum more in detail. I have in my " Recent Researches on Electricity and Magnetism" calculated the amount of momentum at any point in the electric field, and have shown that if N is the number of Faraday tubes passing through a unit area drawn at right angles to their direction, B the magnetic induction, 0 the angle between the induction and the Faraday tubes, then the momentum per unit volume is equal to N B sin 0, the direction of the momentum being at right angles to the mag- netic induction and also to the Faraday tubes. Many of you will notice that the momentum is parallel to what is known as Poynting's vector — the vector whose direction gives the direction in which energy is flowing through the field.

| |

| | |

| Moment of Momentum Due to cm Electrified Point and a Magnetic Pole

| |

| | |

| To familiarize ourselves with this distribution of momentum let us consider some simple cases in detail. Let us begin with the simplest, that of an electrified point and a magnetic pole; let A^ Fig. 7, be the point, B the pole. Then, since the momen-

| |

| | |

| | |

| 26 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| turn at any point P is at right angles to A P, the direction of the Faraday tubes and also to B P, the magnetic induction, we see that the momentum will be perpendicular to the plane A B P ; thus, if we draw a series of lines such that their direc- tion at any point coincides with the direction of the momentum at that point, these lines will form a series of circles whose planes are perpendicular to the line A 12, and whose centres lie along that line. This distribution of momentum, as far as direction goes, is that possessed by a top spin- ning around A B. Let us now find what this distribution of momentum throughout the field is equivalent to. It is evident that the resultant momentum in any direction is zero, but since the system is spinning round A B, the direction of rotation being every- where the same, there will be a finite moment of momentum round A B. Calculating the value of this from the expression for the momentum given above, we obtain the very simple expression em as the value of the moment of momentum about A By e being the charge on the point and m the strength of the pole. By means of this

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 27

| |

| | |

| expression we can at once find the moment of momentum of any distribution of electrified points and magnetic poles.

| |

| | |

| To return to the system of the point and pole, this conception of the momentum of the system leads directly to the evaluation of the force acting on a moving electric charge or a moving magnetic pole. For suppose that in the time 8 t the electri- fied point were to move from A to A! ', the ^ moment of momentum is still em, but ifc/ its axis is along A! IB instead of A B. ^ The moment of momentum of the field \ has thus changed, but the whole moment \ of momentum of the system comprising \ point, pole, and field must be constant, so \ that the change in the moment of momen- \ turn of the field must be accompanied \ by an equal and opposite change in the j moment of momentum of the pole and FlGt 8- point. The momentum gained by the point must be equal and opposite to that gained by the pole, since the whole momentum is zero. If 0 is the angle A £ A , the change in the moment of momentum is em sin 0, with an axis at right angles to A B in the plane of the paper. Let 8 / be the change in the momentum of A, —

| |

| | |

| | |

| 2g ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| 8 I that of B, then 8 / and — 8 1 must be equivalent to a couple whose axis is at right angles to A B in the plane of the paper, and whose moment is e m sin 6. Thus 8 I must be at right angles to the plane of the paper and

| |

| | |

| emAA'sm<f>

| |

| | |

| | |

| Where </> is the angle B A A'. If v is the velocity of A, A Af—v 8 1 and we get

| |

| | |

| | |

| s* T_

| |

| | |

| | |

| e m v sm

| |

| | |

| | |

| AB*

| |

| | |

| This change in the momentum may be sup- posed due to the action of a force F perpen-

| |

| | |

| dicular to the plane of the paper, F being the

| |

| | |

| g 2 rate of increase of the momentum, or -r' We thus

| |

| | |

| | |

| t _ . .

| |

| | |

| get Jb = — A rea ; or the point is acted on by a

| |

| | |

| force equal to e multiplied by the component of the magnetic force at right angles to the direction of motion. The direction of the force acting on the point is at right angles to its velocity and also to the magnetic force. There is an equal and opposite force acting on the magnetic pole.

| |

| | |

| The value we have found for F is the ordinary expression for the mechanical force acting on a moving charged particle in a magnetic field; it

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 29

| |

| | |

| may be written as ev Hsm <£, where H's is the strength of the magnetic field. The force acting on unit charge is therefore v Hsm <f>. This me- chanical force may be thus regarded as arising from an electric force v H sin <f>, and we may express the result by saying that when a charged body is moving in a magnetic field an electric force v If sin <f> is produced. This force is the well-known electromotive force of induction due to motion in a magnetic field.

| |

| | |

| The forces called into play are due to the relative motion of the pole and point; if these are moving with the same velocity, the line joining them will not alter in direction, the moment of momentum of the system will remain unchanged and there will not be any forces acting either on the pole or the point.

| |

| | |

| The distribution of momentum in the system of pole and point is similar in some respects to that in a top spinning about the line A B. We can illustrate the forces acting on a moving elec- trified body by the behavior of such a top. Thus, let Fig. 9 represent a balanced gyroscope spinning about the axis A B, let the ball at A represent the electrified point, that at £ the magnetic pole. Suppose the instrument is spinning with A B

| |

| | |

| | |

| 30 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| horizontal, then if with a vertical rod I push against A B horizontally, the point A will not merely move horizontally forward in the direction in which it is pushed, but will also move verti- cally upward or downward, just as a charged

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. 9.

| |

| | |

| point would do if pushed forward in the same way, and if it were acted upon by a magnetic pole at B.

| |

| | |

| Maxwell's Vector Potential

| |

| | |

| There is a very close connection between the momentum arising from an electrified point and a

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 31

| |

| | |

| magnetic system, and the Vector Potential of that system, a quantity which plays a very large part in Maxwell's Theory of Electricity. From the ex- pression we have given for the moment of mo- mentum due to a charged point and a magnetic pole, we can at once find that due to a charge e of electricity at a point P, and a little magnet A B ; let the negative pole of this magnet be at A, the positive at B, and let m be the strength of either pole. A simple calculation shows that in this case the axis of the resultant moment of momen- tum is in the plane P A B at right angles to P O, O being the middle point of A B, and that the magnitude of the moment of momentum is equal

| |

| | |

| to e. m. A B mi where <£ is the angle A B

| |

| | |

| | |

| makes with O P. This moment of momentum is equivalent in direction and magnitude to that due

| |

| | |

| to a momentum e. in. A B -Qjk at P directed

| |

| | |

| at right angles to the plane P A B, and another momentum equal in magnitude and opposite in

| |

| | |

| direction at O. The vector in A B -m at P

| |

| | |

| | |

| at right angles to the plane P A B is the vector called by Maxwell the Vector Potential at P due to the Magnet.

| |

| | |

| | |

| 32 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| Calling this Vector Potential I, we see that the momentum due to the charge and the magnet is equivalent to a momentum e I at P and a momen- tum — e Tat the magnet.

| |

| | |

| We may evidently extend this to any complex system of magnets, so that if / is the Vector Po- tential at P of this system, the momentum in the field is equivalent to a momentum e I at P to- gether with momenta at each of the magnets equal to

| |

| | |

| — e (Vector Potential at P due to that magnet). If the magnetic field arises entirely from electric currents instead of from permanent magnets, the momentum of a system consisting of an electrified point and the currents will differ in some of its features from the momentum when the magnetic field is due to permanent magnets. In the latter case, as we have seen, there is a moment of mo- mentum, but no resultant momentum. When, however, the magnetic field is entirely due to electric currents, it is easy to show that there is a resultant momentum, but that the moment of mo- mentum about any line passing through the elec- trified particle vanishes. A simple calculation shows that the whole momentum in the field is equivalent to a momentum e I at the electrified

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 33

| |

| | |

| point I being the Vector Potential at P due to the currents.

| |

| | |

| Thus, whether the magnetic field is due to per- manent magnets or to electric currents or partly to one and partly to the other, the momentum when an electrified point is placed in the field at P is equivalent to a momentum e Tat P where I is the Vector Potential at P. If the magnetic field is entirely due to currents this is a complete representation of the momentum in the field ; if the magnetic field is partly due to magnets we have in addition to this momentum at P other momenta at these magnets ; the magnitude of the momentum at any particular magnet is — e times the Vector Potential at P due to that magnet.

| |

| | |

| The well-known expressions for the electro- motive forces due to Electro-magnetic Induction follow at once from this result. For, from the Third Law of Motion, the momentum of any self- contained system must be constant. Now the momentum consists of (1) the momentum in the field ; (2) the momentum of the electrified point, and (3) the momenta of the magnets or circuits carrying the currents. Since (1) is equivalent to a momentum e 1 at the electrified particle, we see that changes in the momentum of the field must

| |

| | |

| | |

| 34 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| be accompanied by changes in the momentum of the particle. Let M be the mass of the electrified particle, u, v, w the components parallel to the axes of #, y, z of its velocity, F, G, U, the com- ponents parallel to these axes of the Vector Po- tential at P, then the momentum of the field is equivalent to momenta eF, e G, eH at P parallel to the axes of a?, y, z ; and the momentum of the charged point at P has for components Mu, Mty Mw. As the momentum remains constant, Mu -f- e F\* constant, hence if 8w and §F are simulta- neous changes in u and F,

| |

| | |

| MSu + e§F= 0;

| |

| | |

| <*«**« -4*

| |

| | |

| dt dt

| |

| | |

| From this equation we see that the point with the charge behaves as if it were acted upon by a me. chanical force parallel to the axis of x and equal to

| |

| | |

| - e -=-, i.e., by an electric force equal to - —=— In a similar way we see that there are electric forces — -j — } -. -j—} parallel to y and z respec- tively. These are the well-known expressions of the forces due to electro-magnetic induction, and we see that they are a direct consequence of the

| |

| | |

| | |

| LINES OF FORCE 35

| |

| | |

| principle that action and reaction are equal and opposite.

| |

| | |

| Headers of Faraday's Experimental Researches will remember that he is constantly referring to what he called the " Electrotonic State " ; thus he regarded a wire traversed by an electric current as being in the Electrotonic State when in a magnetic field. No effects due to this state can be detected as long as the field remains constant ; it is when it is changing that it is operative. This Electrotonic State of Faraday is just the momen- tum existing in the field.

| |

| | |

| | |

| ==CHAPTER II==

| |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL AND BOUND MASS.

| |

| | |

| I WISH in this chapter to consider the connec- tion between the momentum in the electric field and the Faraday tubes, by which, as I showed in the last lecture, we can picture to ourselves the state of such a field. Let us begin by considering the case of the moving charged sphere. The lines of electric force are radial : those of magnetic force are circles having for a common axis the line of mo- tion of the centre of the sphere ; the momentum

| |

| | |

| at a point P is at right angles to each of these directions and so is at right angles to O P in the plane containing P and the line of motion FlG- ia of the centre of the

| |

| | |

| sphere. If the number of Faraday tubes passing through a unit area at P placed at right angles to 0 P is N, the magnetic induction at P is, if /a is the magnetic permeability of the medium

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 37

| |

| | |

| surrounding the sphere, ±TrpNv sin 0, v being the velocity of the sphere and 0 the angle O P makes with the direction of motion of the sphere. By the rule given on page 25 the momentum in unit volume of the medium at P is NX ±TrpNv sin 0, or ^n^N*v sin 0, and is in the direction of the component of the veloc- ity of the Faraday tubes at right angles to their length. Now this is exactly the momentum which would be produced if the tubes were to carry with them, when they move at right angles to their length, a mass of the surrounding medium equal to 4?r /x N* per unit volume, the tubes pos- sessing no mass themselves and not carrying any of the medium with them when they glide through it parallel to their own length. We suppose in fact the tubes to behave veiy much as long and narrow cylinders behave when moving through water ; these if moving endwise, i.e., par- allel to their length, carry very little water along with them, while when they move sideways, i.e., at right angles to their axis, each unit length of the tube carries with it a finite mass of water. When the length of the cylinder is veiy great compared with its breadth, the mass of water carried by it when moving endwise may be neglected in com-

| |

| | |

| | |

| gg ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| parison with that carried by it when moving side- ways ; if the tube had no mass beyond that which it possesses in virtue of the water it displaces, it would have mass for sideways but none for end- wise motion.

| |

| | |

| We shall call the mass 4?r /i Nz carried by the tubes in unit volume the mass of the bound ether. It is a very suggestive fact that the electrostatic energy E in unit volume is proportional to M the mass of the bound ether in that volume. This can

| |

| | |

| 27rJV2 easily be proved as follows : E = — ==- , where

| |

| | |

| K is the specific inductive capacity of the medium ; while M = 4?r /u, N*, thus,

| |

| | |

| | |

| but ~~j^— V* where V is the velocity with which light travels through the medium, hence

| |

| | |

| | |

| thus E is equal to the kinetic energy possessed by the bound mass when moving with the veloc- ity of light.

| |

| | |

| The mass of the bound ether in unit volume is 47r/u,j\^2 where N\& the number of Faraday tubes ; thus, the amount of bound mass per unit length of

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS

| |

| | |

| | |

| each Farkday tube is 4?r pN. We have seen that this is proportional to the tension in each tube, so that we may regard the Faraday tubes as tightly stretched strings of variable mass and tension ; the tension being, however, always proportional to the mass per unit length of the string.

| |

| | |

| Since the mass of ether imprisoned by a Faraday tube is proportional to N the number of Faraday tubes in unit volume, we see that the mass and momentum of a Faraday tube depend not merely upon the configuration and velocity of the tube under consideration, but also upon the number and velocity of the Faraday tubes in its neigh- borhood. We have many analogies to this in the case of dynamical systems ; thus, in the case of a number of cylinders with their axes parallel, mov- ing about in an incompressible liquid, the momen- tum of any cylinder depends upon the positions and velocities of the cylinders in its neighborhood. The following hydro-dynamical system is one by which we may illustrate the fact that the bound mass is proportional to the square of the number of Faraday tubes per unit volume.

| |

| | |

| Suppose we have a cylindrical vortex column of strength m placed in a mass of liquid whose ve- locity, if not disturbed by the vortex column, would

| |

| | |

| | |

| 40

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| | |

| be constant both in magnitude and direction, and at right angles to the axis of the vortex column. The lines of flow in such a case are represented in Fig. 11, where A is the section of the vortex

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. 11.

| |

| | |

| column whose axis is supposed to be at right an- gles to the plane of the paper. We see that some of these lines in the neighborhood of the column are closed curves. Since the liquid does not cross the lines of flow, the liquid inside a closed curve will always remain in the neighborhood of the col- umn and will move with it. Thus, the column will imprison a mass of liquid equal to that en- closed by the largest of the closed lines of flow. If m is the strength of the vortex column and a the velocity of the undisturbed flow of the liquid, we can easily show that the mass of liquid imprisoned

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 41

| |

| | |

| •

| |

| | |

| by the column is proportional to ~. Thus, if

| |

| | |

| CL

| |

| | |

| we take m as proportional to the number of Faraday tubes in unit area, the system illustrates the connection between the bound mass and the strength of the electric field.

| |

| | |

| Affective of Velocity on tJie Sound Mass

| |

| | |

| I will now consider another consequence of the idea that the mass of a charged particle arises from the mass of ether bound by the Faraday tube as- sociated with the charge. These tubes, when they move at right angles to their length, carry with them an appreciable portion of the ether through which they move, while when they move parallel to their length, they glide through the fluid with- out setting it in motion. Let us consider how a long, narrow cylinder, shaped like a Faraday tube, would behave when moving through a liquid.

| |

| | |

| Such a body, if free to twist in any direction, will not, as you might expect at first sight, move point foremost, but will, on the contrary, set itself broadside to the direction of motion, setting itself so as to carry with it as much of the fluid through which it is moving as possible. Many illustra- tions of this principle could be given, one very

| |

| | |

| | |

| 42 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| familiar one is that falling leaves do not fall edge first, but flutter down with their planes more or less horizontal.

| |

| | |

| If we apply this principle to the charged sphere, we see that the Faraday tubes attached to the sphere will tend to set themselves at right angles to the direction of motion of the sphere, so that if this principle were the only thing to be considered all the Faraday tubes would be forced up into the equatorial plane, i.e., the plane at right angles to the direction of motion of the sphere, for in this position they would all be moving at right angles to their lengths. We must remember, however, that the Faraday tubes repel each other, so that if they were crowded into the equatorial region the pressure there would be greater than that near the pole. This would tend to thrust the Faraday tubes back into the position in which they are equally distributed all over the sphere. The actual distribution of the Faraday tubes is a com- promise between these extremes. They are not all crowded into the equatorial plane, neither are they equally distributed, for they are more in the equatorial regions than in the others ; the excess of the density of the tubes in these regions increasing with the speed with which the charge is moving.

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 43

| |

| | |

| When a Faraday tube is in the equatorial region it imprisons more of the ether than when it is near the poles, so that the displacement of the Faraday tubes from the pole to the equator will increase the amount of ether imprisoned by the tubes, and therefore the mass of the body.

| |

| | |

| It has been shown (see Heaviside, Phil. Mag., April, 1889, "Recent Researches," p. 19) that the effect of the motion of the sphere is to displace each Faraday tube toward the equatorial plane, i.e., the plane through the centre of the sphere at right angles to its direction of motion, in such a way that the projection of the tube on this plane remains the same as for the uniform distribution of tubes, but that the distance of every point in the tube from the equatorial plane is reduced in the proportion of V V*-v* to V, where V is the veloc- ity of light through the medium and v the velocity of the charged body.

| |

| | |

| From this result we see that it is only when the velocity of the charged body is comparable with the velocity of light that the change in distribu- tion of the Faraday tubes due to the motion of the body becomes appreciable.

| |

| | |

| In " Recent Researches on Electricity and Mag- netism," p. 21, 1 calculated the momentum I, in the

| |

| | |

| | |

| 44 ELECTRICITY AND MATTKK

| |

| | |

| space surrounding a sphere of radius a, having its centre at the moving charged body, and showed that the value of /is given by the following expression :

| |

| | |

| | |

| cos

| |

| | |

| | |

| 20)1 ;..(!)

| |

| | |

| | |

| where as before v and V are respectively the ve- locities of the particle and the velocity of light, and 6 is given by the equation

| |

| | |

| v sm 6 = j^.

| |

| | |

| The mass of the sphere is increased in conse- quence of the charge by - , and thus we see from

| |

| | |

| equation (1) that for velocities of the charged body comparable with that of light the mass of the body will increase with the velocity. It is evident from equation (1) that to detect the influ- ence of velocity on mass we must use exceed- ingly small particles moving with very high ve- locities. Now, particles having masses far smaller than the mass of any known atom or molecule are shot out from radium with velocities ap- proaching in some cases to that of light, and the ratio of the electric charge to the mass for parti-

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 45

| |

| | |

| cles of this kind has lately been made the subject of a very interesting investigation by Kaufmann, with the results shown in the following table ; the first column contains the values of the velocities of the particle expressed in centimetres per sec- ond, the second column the value of the fraction

| |

| | |

| — where e is the charge and m the mass of the particle :

| |

| | |

| v X 10-10 1 X 10-7

| |

| | |

| 2.83 .62

| |

| | |

| 2.72 .77

| |

| | |

| 2.59 .975

| |

| | |

| 2.48 1.17

| |

| | |

| 2.36 1.31

| |

| | |

| We see from these values that the value of — di-

| |

| | |

| m

| |

| | |

| minishes as the velocity increases, indicating, if we suppose the charge to remain constant, that the mass increases with the velocity. Kauf mann's results give us the means of comparing the part of the mass due to the electric charge with the part independent of the electrification ; the second part of the mass is independent of the velocity. If then we find that the mass varies appreciably with the velocity, we infer that the part of the

| |

| | |

| | |

| 46 ELECTRICITY AND MATTKI!

| |

| | |

| mass due to the charge must be appreciable in comparison with that independent of it. To cal- culate the effect of velocity on the mass of an electrified system we must make some assump- tion as to the nature of the system, for the effect on a charged sphere for example is not quite the same as that on a charged ellipsoid ; but having made the assumption and calculated the theoretical effect of the velocity on the mass, it is easy to de- duce the ratio of the part of the mass independent of the charge to that part which at any velocity de- pends upon the charge. Suppose that the part of the mass due to electrification is at a velocity v equal to m0f(v) where f(v) is a known function of v, then if Mv, Mvi are the observed masses at the velocities v and v1 respectively and M the part of the mass independent of charge, then

| |

| | |

| | |

| two equations from which M and m0 can be de- termined. Kaufmann, on the assumption that the charged body behaved like a metal sphere, the distribution of the lines of force of which when moving has been determined by G. F. C. Searle, came to the conclusion that when the parti- cle was moving slowly the " electrical mass " was

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 47

| |

| | |

| about one-fourth of the whole mass. He was care- ful to point out that this fraction depends upon the assumption we make as to the nature of the moving body, as, for example, whether it is spheri- cal or ellipsoidal, insulating or conducting; and that with other assumptions his experiments might show that the whole mass was electrical, which he evidently regarded as the most probable result.

| |

| | |

| In the present state of our knowledge of the constitution of matter, I do not think anything is gained by attributing to the small negatively charged bodies shot out by radium and other bodies the property of metallic conductivity, and I prefer the simpler assumption that the distribu- tion of the lines of force round these particles is the same as that of the lines due to a charged point, provided we confine our attention to the field outside a small sphere of radius a having its centre at the charged point ; on this supposition the part of the mass due to the charge is the value

| |

| | |

| of — in equation (1) on page 44. I have calcu- lated from this expression the ratio of the masses of the rapidly moving particles given out by ra- dium to the mass of the same particles when at rest, or moving slowly, on the assumption that the

| |

| | |

| | |

| 4g ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| whole of the mass is due to th^ charge and have com- pared these results with the values of the same ratio as determined by Kaufmann's experiments. These results are given in Table (II), the first col- umn of which contains the values of v, the veloci- ties of the particles ; the second p, the number of times the mass of a particle moving with this ve- locity exceeds the mass of the same particle when at rest, determined by equation (1) ; the third column p\ the value of this quantity found by Kaufmann in his experiments.

| |

| | |

| | |

| TABLE

| |

| | |

| ii.

| |

| | |

| • io-10 cm

| |

| | |

| P 3.1

| |

| | |

| P1 3.09

| |

| | |

| > -1-vJ

| |

| | |

| sec 2.85

| |

| | |

| 2.72

| |

| | |

| 2.42

| |

| | |

| 2.43

| |

| | |

| 2.59

| |

| | |

| 2.0

| |

| | |

| 2.04

| |

| | |

| 2.48

| |

| | |

| 1.66

| |

| | |

| 1.83

| |

| | |

| 2.36

| |

| | |

| 1.5

| |

| | |

| 1.65

| |

| | |

| These results support the view that the whole mass of these electrified particles arises from their charge.

| |

| | |

| We have seen that if we regard the Faraday tubes associated with these moving particles as being those due to a moving point charge, and

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 49

| |

| | |

| confine our attention to the part of the field which is outside a sphere of radius a concentric with the charge, the mass m due to the charge e on the particle is, when the particle is moving slowly,

| |

| | |

| given by the equation m = -$ — •

| |

| | |

| In a subsequent lecture I will explain how the values of me and e have been deter- mined ; the result of these determinations is that

| |

| | |

| 5 = 10-T and e = 1.2 X lO'80 in C. G. S. elec- e

| |

| | |

| trostatic units. Substituting these values in the expression for m we find that a is about 5 X 10~14 cm, a length very small in comparison with the value 10"8 c m, which is usually taken as a good approximation to the dimensions of a molecule.

| |

| | |

| We have regarded the mass in this case as due to the mass of ether carried along by the Faraday tubes associated with the charge. As these tubes stretch out to an infinite distance, the mass of the particle is as it were diffused through space, and has no definite limit. In consequence, however, of the very small size of the particle and the fact that the mass of ether carried by the tubes (being proportional to the square of the density of the Faraday tubes) varies inversely as the fourth

| |

| | |

| | |

| 50 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| power of the distance from the particle, we find by a simple calculation that all but the most insig- nificant fraction of mass is confined to a distance from the particle which is very small indeed com- pared with the dimensions ordinarily ascribed to atoms.

| |

| | |

| In any system containing electrified bodies a part of the mass of the system will consist of the mass of the ether carried along by the Faraday tubes associated with the electrification. Now one view of the constitution of matter — a view, I hope to discuss in a later lecture — is that the atoms of the various elements are collections of positive and negative charges held together mainly by their electric attractions, and, moreover, that the negatively electrified particles in the atom (corpuscles I have termed them) are identical with those small negatively electrified particles whose properties we have been discussing. On this view of the constitution of matter, part of the mass of any body would be the mass of the ether dragged along by the Faraday tubes stretching across the atom between the positively and negatively electrified constituents. The view I wish to put before you is that it is not merely a part of the mass of a body which arises in this

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICAL MASS 51

| |

| | |

| way, but that the whole mass of any body is just the mass of ether surrounding the body which is carried along by the Faraday tubes associated with the atoms of the bodj^. In fact, that all mass is mass of the ether, all momentum, momentum of the ether, and all kinetic energy, kinetic energy of the ether. This view, it should be said, requires the density of the ether to be immensely greater than that of any known substance.

| |

| | |

| It might be objected that since the mass has to be carried along by the Faraday tubes and since the disposition of these depends upon the relative position of the electrified bodies, the mass of a collection of a number of positively and negatively electrified bodies would be constantly changing with the positions of these bodies, and thus that mass instead of being, as observation and experi- ment have shown, constant to a very high degree of approximation, should vary with changes in the physical or chemical state of the body.

| |

| | |

| These objections do not, however, apply to such a case as that contemplated in the preceding theory, where the dimensions of one set of the electrified bodies — the negative ones — are excessively small in comparison with the distances separating the various members of the system of electrified bodies.

| |

| | |

| | |

| 52 ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| When this is the case the concentration of the lines of force on the small negative bodies — the corpuscles — is so great that practically the whole of the bound ether is localized around these bodies, the amount depending only on their size and charge. Thus, unless we alter the number or character of the corpuscles, the changes occurring in the mass through any alteration in their rela- tive positions will be quite insignificant in com- parison with the mass of the body.

| |

| | |

| | |

| ==CHAPTER III==

| |

| | |

| EFFECTS DUE TO ACCELERATION OF THE FARADAY TUBES

| |

| | |

| Rontgen Rays and Light

| |

| | |

| WE have considered the behavior of the lines of force when at rest and when moving uniformly, we shall in this chapter consider the phenomena which result when the state of motion of the lines is changing.

| |

| | |

| Let us begin with the case of a moving charged point, moving so slowly that the lines of force are uniformly distributed around it, and consider what must happen if we suddenly stop the point. The Faraday tubes associated with the sphere have inertia; they are also in a state of tension, the tension at any point being proportional to the mass per unit length. Any disturbance communicated to one end of the tube will therefore travel along it with a constant and finite velocity ; the tube in fact having very considerable analogy with a stretched string. Suppose we have a tightly stretched vertical string moving uniformly, from

| |

| | |

| | |

| 54

| |

| | |

| | |

| ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| | |

| right to left, and that we suddenly stop one end, A, what will happen to the string ? The end A will come to rest at once, but the forces called into play travel at a finite rate, and each part of the string will in virtue of its inertia continue to move as if nothing had happened to the end A until the disturbance starting from A reaches it. Thus, if V is the velocity with which a disturb- ance travels along the string, then when a time, t, has elapsed after the stoppage of A, the parts of the string at a greater distance than Vt from A will be unaffected by the stoppage, and will have the position and velocity they would have had if the string had continued to move uniformly forward. The shape of the string at successive intervals will be as shown in Fig. 12, the length of

| |

| | |

| | |

| j

| |

| | |

| | |

| A Fio. 12.

| |

| | |

| | |

| the horizontal portion increasing as its distance from the fixed end increases.

| |

| | |

| | |

| RONTGEN RAYS AND LIGHT 55

| |

| | |

| Let us now return to the case of the moving charged particle which we shall suppose suddenly brought to rest, the time occupied by the stoppage being T. To find the configuration of the Faraday tubes after a time t has elapsed since the beginning of the process of bringing the charged particle to rest, describe with the charged particle as centre two spheres, one having the radius Vt, the other the radius V(t — T), then, since no disturbance can have reached the Faraday tubes situated outside the outer sphere, these tubes will be in the posi- tion they would have occupied if they had moved forward with the velocity they possessed at the moment the particle was stopped, while inside the inner sphere, since the disturbance has passed over the tubes, they will be in their final positions. Thus, consider a tube which, when the particle was stopped was along the line OPQ (Fig. 13) ; this will be the final position of the tube ; hence at the time t the portion of this tube inside the inner sphere will occupy the position OP, while the portion P'Q' outside the outer sphere will be in the position it would have occupied if the particle had not been reduced to rest, i.e., if O ' is the position the particle would have occupied if it had not been stopped, P'Q' will be a straight line pass-

| |

| | |

| | |

| gg ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |

| ing through 0 '. Thus, to preserve its continuity the tube must bend round in the shell between the two spheres, and thus be distorted into the shape OPP'Q'. Thus, the tube which before the stop-

| |

| | |

| | |

| FIG. 13.

| |

| | |

| page of the particle was radial, has now in the shell a tangential component, and this tangential component implies a tangential electric force. The stoppage of the particle thus produces a radical change in the electric field due to the par- ticle, and gives rise, as the following calculation will show, to electric and magnetic forces much greater than those existing in the field when the particle was moving steadily.

| |

| | |

| If we suppose that the thickness 8 of the shell is so small that the portion of the Faraday tube inside it may be regarded as straight, then if T is

| |

| | |

| | |

| RONTGEN RAYS AND LIGHT 57

| |

| | |

| the tangential electric force inside the pulse, R the radial force, we have

| |

| | |

| T P'R 00' sin 0 v t sin 0

| |

| | |

| | |

| Where v is the velocity with which the particle was moving before it was stopped, d the angle OP makes with the direction of motion of the particle, t the time which has elapsed since the par-

| |

| | |

| ticle was stopped ; since R = -y™ and 0 P =Vt where Fis the velocity of light, we have, if r = OP,

| |

| | |

| /TT ev sin 0 f .

| |

| | |

| = TTS~-

| |

| | |

| The tangential Faraday tubes moving forward with the velocity Fwill produce at P a magnetic force If equal to V T, this force will be at right angles to the plane of the paper and in the opposite direction to the magnetic force existing at P before the stoppage of the particle ; since its magnitude is given by the equation,

| |

| | |

| „ evsinO

| |

| | |

| •"• — --- ^ — > ro

| |

| | |

| . . f ev sin 0 . , it exceeds the magnetic force — -z — previously

| |

| | |

| existing in the proportion of r to S. Thus, the

| |

| | |

| | |

| gg ELECTRICITY AND MATTER

| |

| | |